My daughter gave me Norman Podhoretz’s classic memoir Making It for Christmas. Podhoretz was, inter alia, the influential editor of the American political and cultural magazine Commentary for a number of years, a post now occupied by his son John. Back in the heyday of political blogging, a decade or so ago, I remember being shocked to see one of my blogging friends – part of our loose liberal-interventionist / anti-totalitarian-leftist group whose leading light was the late Norm Geras – linking to articles in Commentary, then the leading journal of American neoconservatism. Well, in the intervening years, the world has changed, and I’ve changed too, and I’m now a regular reader of Commentary, and an avid listener to its (formerly twice-weekly but currently daily) podcast. A couple of years ago I was thrilled when another old blogging friend, Sohrab Ahmari, joined the journal and became a regular contributor to the podcast (this was soon after I met Sohrab in London, when he was working over here for the Wall Street Journal, and shortly before he returned to the States to take up his new post: since then Sohrab has moved on to the New York Post, and has become a key figure in debates about the future of both conservatism and Catholicism: about which more perhaps on another occasion).

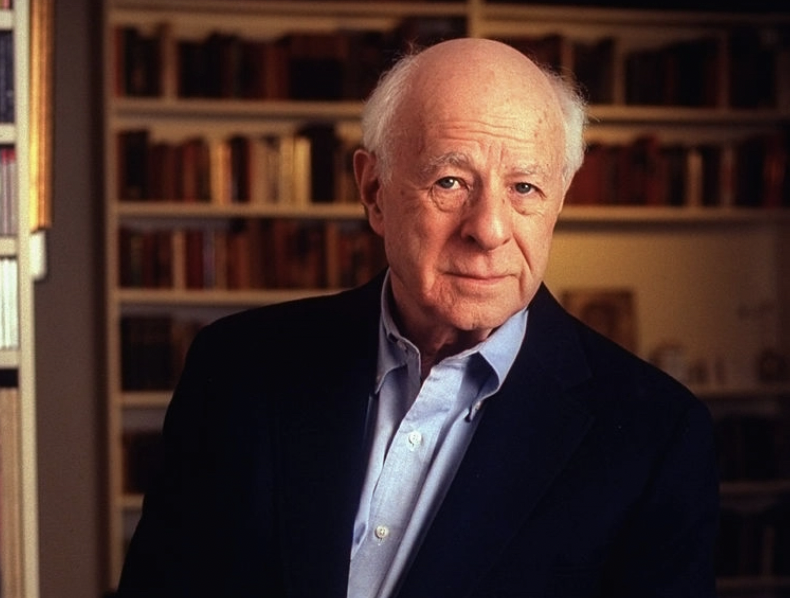

Norman Podhoretz (via Commentary)

Podhoretz senior’s book provides fascinating insights into the American intellectual and cultural milieu in the post-war period, but it’s also an account of his personal social and intellectual journey from working-class Jewish Brooklyn, first to academic success and then to acceptance into the ‘family’ of the New York intelligentsia. I was intrigued to discover that, for Podhoretz as for me, the escape route was via the study of English literature. And that wasn’t the only point of resonance with my experience. I’m not American, or Jewish, but when I read the passage below, Neil Diamond’s immortal words (in his 1971 hit I Am, I Said ) came immediately to mind: ‘Well except for the names / And a few other changes / If you talk about me / The story’s the same one’:

Oddly enough for a boy of literary bent, I had read almost nothing before Columbia but popular novels and a few of the standard poets. I had never heard of most of the books we were given to read in Humanities and Contemporary Civilization – the two great freshman courses for which the college is deservedly famous – let alone of the modern authors whose names were being dropped so casually all around me. Though I had been writing poems and stories ever since I could remember, I did not know what men were doing when they committed words to paper. I did not know that there was more to a poem than verbal prettiness and passion, or that there was more to a novel than a story. I did not know what an idea was or how the mind could play with it. I did not know what history was, thinking of it as a series of isolated past events which had been arbitrarily selected for inclusion in the dreary canon of required knowledge. I did not know that I was the product of a tradition, that past ages had been inhabited by men like myself, and that the things they had done bore a direct relation to me and to the world in which I lived. All this began at Columbia and it set my brain on fire.

Substitute ‘Cambridge’ for ‘Columbia’, a London overspill housing estate in Essex for Brooklyn, and that’s my story, right there. For example: I remember my Cambridge supervisor prefacing a discussion of Yeats’ ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ with the words, ‘Well, of course, this is a poem one has known since one was fourteen’: I’d read it for the first time the night before. Like Podhoretz, I was taken up and promoted by a sympathetic schoolteacher because I was ‘good at English’: but I didn’t read much ‘proper’ literature, and certainly didn’t learn how to read – or think – until I got to university. In my case, it was Cambridge (where, as it happens, Podhoretz came to study, after Columbia, attending seminars with F.R.Leavis at Downing, the college where I’d find a home two decades later) that ‘set my brain on fire’ – and I’ve never looked back.